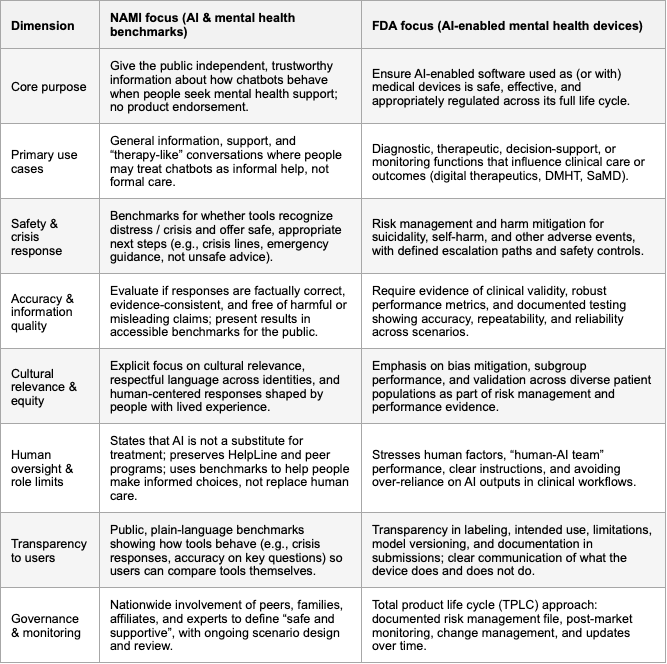

Comparing FDA and NAMI Expectations for AI

NAMI and the FDA are arriving at the same core message about AI in mental health: these tools must be safe, limited in what they claim to do, and grounded in human care rather than replacing it. Both organizations are approaching the problem from different angles, NAMI as a lived‑experience, grassroots mental health organization and the FDA as a medical regulator, but they converge on a surprisingly similar set of expectations for any AI that touches mental health. In practice, this means AI systems will increasingly be judged not just on how “smart” they are, but on how they behave in moments of vulnerability, how they handle risk, and how they respect the people using them.

The first shared pillar is crisis safety. NAMI has made crisis detection and response the top item in its benchmark scope: tools should recognize when someone may be in distress and offer appropriate, safe next steps, including crisis lines and human help. The FDA, when it looks at AI that could function as a medical device or influence care decisions, focuses on risk management, adverse events, and clear escalation pathways for situations like suicidality or self‑harm. In both frames, an AI that misses a crisis, or responds in an unsafe, dismissive, or confusing way, is unacceptable, regardless of how good its reasoning or small‑talk may otherwise be.

The second shared concern is accuracy and the avoidance of harm. NAMI emphasizes whether responses are factually correct, consistent with evidence, and free of harmful or misleading claims, because the public cannot easily tell a plausible hallucination from a trustworthy answer. The FDA expresses the same idea through requirements for clinical validity, reliability, and ongoing performance monitoring: claims must be supported by evidence, and the system must keep behaving as intended over time. Both perspectives are reacting to the same risk: AI that sounds confident but gives dangerous or misleading mental health advice.

Another strong area of overlap is human context: cultural relevance, boundaries, and human factors. NAMI explicitly calls for cultural relevance and human‑centered language across identities and lived experiences; it also insists that AI is not a replacement for care and should not displace helplines, programs, or human support. The FDA, in its own way, focuses on human factors engineering, usability, and safeguards against over‑reliance on AI, especially in sensitive therapeutic contexts. Both essentially want systems that are respectful, understandable, and that consistently remind people where the limits of AI support lie.

Our SASI middeware already implements several of these shared expectations as first‑class design constraints. It runs pre‑LLM crisis detection with explicit crisis types, severity, recommended actions, and crisis resources; it enforces configurable safety tiers and modes for different contexts (child, patient, therapist, mental health support, general assistant); it performs PII redaction before external calls; it detects adversarial patterns and obfuscation; and it exposes structured metadata for escalation to humans when uncertainty or risk is high. In other words, SASI already covers much of the common NAMI/FDA safety core: crisis sensitivity, harm reduction, privacy, boundaries, and human‑in‑the‑loop routing, and is designed to act as the safety layer that many AI mental health tools will need in order to meet these converging expectations.